Boletín Nº 6060

Katrina redefined hurricane risk for insurance sector

When Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast in 2005, it caused death and catastrophic damage in Louisiana and surrounding states despite weakening to Category 3 just before landfall.

The storm also was a turning point for how the insurance industry assessed the potential for hurricanes to cause extensive damage, not just from wind but from storm surge combined with catastrophic flooding due to the failure of the levee and floodwall systems in New Orleans.

Twenty years later, Katrina remains one of the deadliest hurricanes to have hit the U.S. Initial estimates put its death toll at more than 1,800 people, but the National Hurricane Center later revised that to just under 1,400.

After Katrina, the U.S. government invested tens of billions of dollars to strengthen flood defenses in New Orleans, which sits mostly below sea level, and stricter building codes were adopted in Louisiana and Mississippi to improve storm resilience.

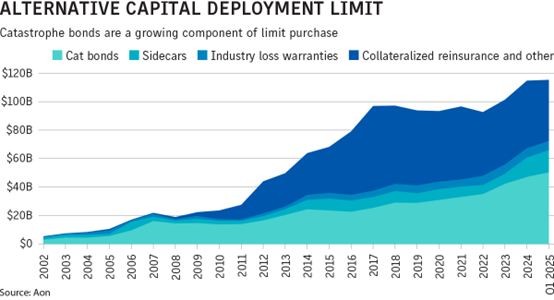

Catastrophe modeling, which the industry widely adopted after Hurricane Andrew in 1992, evolved to incorporate improved data and new techniques (see related story below). The underwriting and pricing of catastrophe risk fundamentally shifted, leading to stricter terms and conditions for policyholders. The property catastrophe reinsurance market in Bermuda expanded, and demand for alternative capital increased (see story below).

Katrina made landfall near Buras, Louisiana, on Aug. 29, 2005. It later struck again — still as a Cat 3 — near the Louisiana-Mississippi border. Previously, it had made landfall just north of Miami before strengthening into a Category 5 hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. The massive storm surge caused by Katrina was attributed to the hurricane’s large size, affecting nearly 93,000 square miles of the U.S.

Katrina dealt a severe blow to the economy and the environment by disrupting key population and tourism hubs, oil and gas operations, and transportation. Workplaces in New Orleans and beyond were damaged, resulting in thousands of job losses and millions of dollars in lost tax revenue. Over 800,000 housing units were damaged or destroyed, and many residents who left New Orleans did not return.

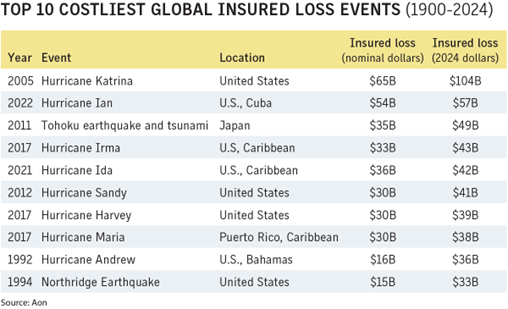

Katrina still ranks as the world’s costliest insured loss since 1900, causing $65 billion in covered losses at the time (see chart above).

Catastrophic losses

Katrina was a “watershed moment” for the industry, said Mohit Pande, New York-based chief underwriting officer, property, at Swiss Re, who in 2005 was a senior research engineer at catastrophe modeler Applied Insurance Research, which became AIR Worldwide.

“It truly reshaped how we understand and manage cat risk,” he said.

Mr. Pande, who led a team of engineers conducting post-disaster damage surveys in Biloxi and Gulfport, Mississippi, remembers seeing large floating casinos washed up inland. “I have not witnessed that kind of devastation in my life before,” he said.

The failure of the levees in New Orleans highlighted the potential for so-called “super cat” effects, Mr. Pande said. “These are compounding factors that drive losses and extreme catastrophes. Some people may also call them black swan events, but these are now routinely incorporated into catastrophe models,” he said.

Public entities with massive property schedules and billions of dollars in values often were covered by just one insurer in the admitted market before Katrina, said Nancy Sylvester, Baton Rouge, Louisiana-based executive area vice president in Arthur J. Gallagher & Co.’s public sector and K-12 education practice.

After the storm, there was a shift toward multi-insurer policies, with more international market involvement, she said.

Katrina was unique in that the flooding led to a long period of inaccessibility in New Orleans and the surrounding region, said Robert O’Brien, a Washington-based managing director in Marsh’s national property claims group.

The severity of damage across a widespread area, the exodus of people from New Orleans and infrastructure issues delayed recovery efforts, he said.

In addition to physical damage, businesses suffered contingent business interruption losses because of supply chain disruptions and the economic effects of a reduced customer base resulting from people leaving the area, Mr. O’Brien said.

“Katrina had a very long tail, not only because it was and remains the largest natural disaster in the U.S. in current dollars, but also in terms of claims,” said Robert P. Hartwig, a professor of finance and director of the Center for Risk and Uncertainty Management at the Darla Moore School of Business at the University of South Carolina.

The hurricane resulted in 1.7 million claims, he said.

Legal battles

Katrina triggered widespread litigation over wind versus flood damage. Most standard property policies exclude flood damage, but separate coverage is available through the National Flood Insurance Program or from private insurers.

The most litigated coverage issue was flood versus wind, said Cliff Simpson, Atlanta-based executive managing director at Brown & Brown. “The insurance industry actually won most of those cases,” he said.

In response to the litigation, insurers tightened definitions of flood and named windstorm in property policies to clarify that storm surge is considered part of flood, Mr. Simpson said.

Insurers also reduced their supplemental flood coverage limits. “Where a carrier might have consistently given $25 million of high-hazard flood on their policy to a single client, they lowered those to $5 million or $10 million to control their exposure,” he said.

As a result, it took more insurers and many more policies to build up the limits that either policyholders felt they needed or that their lenders required, he said.

Policy language was changed and awareness of flood risk increased, said Lauren Savage, Miami-based president of the private flood division at Tokio Marine Highland. Agents now explicitly advise their customers about flood coverage exclusions, she said.

Market changes

Property rates surged after Katrina because of the scale of the losses, as insurers and reinsurers pulled back limits and reevaluated how they modeled, underwrote and priced catastrophe risks.

The price of U.S. property catastrophe reinsurance jumped 76% at January 2006 renewals, according to the rate on line index from Guy Carpenter & Co.

There was an adjustment in pricing across the industry, Mr. Pande said. “Pricing reacted to the adjustment in the underlying exposures,” he said.

Property rates before Katrina were “irresponsibly inexpensive” and there was abundant choice, said Shaun Norris, New Orleans-based president of the Gulf South region at Hub.

“In hindsight, when you look at it, it was far below what we call the expected probable maximum loss, which then caused an unreasonable over-correction in pricing after Katrina,” he said.

The market shifted from standard market coverage to mostly excess and surplus lines quotes after Katrina, he said. “All the bells and whistles an agent could ask for pre-Katrina” became non-negotiable, for instance off-premises power coverage, Mr. Norris said.

Percentage deductibles became standard, especially for catastrophe coverage.

“I had clients during Katrina with a $100,000 property deductible, which feels free right now. Following Katrina, percentage deductibles became the norm and still are,” said Gallagher’s Ms. Sylvester.

Determining how percentage deductibles applied became essential. Many policies defined deductibles on a location basis, meaning all owned buildings within one city block could be treated as a single location, and the deductible applied to the total insured value of all buildings in that location, she said.

“Public entities don’t have the money to pay that kind of deductible, so we try really hard to make sure the deductible is written on a per-building basis,” Ms. Sylvester said.

Technology improves

Advances in technology since Katrina give claims professionals “early eyes” on hurricane losses and allow them to prioritize where their resources will be used, Mr. O’Brien said.

“Today, we can fly drones over a disaster area. We can use satellite photos, any number of tools that we have now that we really didn’t have efficient use of back then,” he said.

Technology enables the industry to assess the overall magnitude of the loss much more quickly, he said.

Advances in technology, such as video surveillance and remote sensors, can improve causation analysis in insurance claims, said Joshua Gold, a shareholder in law firm Anderson Kill’s New York office.

“Back in 2005, that evidence understandably was lacking on a lot of occasions, especially with residential policyholders. In 2025, we’re probably better situated to have more video evidence, more sophisticated data points that we could rely upon if we’re going to have this dichotomy of analysis as to what is actually causing the damage,” he said.

Flood mitigation and property-level resilience became crucial after Katrina, said Jeremy Kiefer, Tampa, Florida-based founder, CEO and executive risk consultant at loss adjusting company Deft Group.

New Orleans and Louisiana invested $14.5 billion after Katrina to rebuild and upgrade the city’s levee system. The Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System, built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and completed in 2018, is designed to protect the region from a 100-year storm surge event.

“With rising sea temperatures, which I don’t think anybody can deny, storms are more severe,” and sea levels are rising, Mr. Kiefer said.

Exposure growth in coastal areas due to demographic shifts is also a growing concern, he said.

“The entire Gulf Coast and Eastern Seaboard is more susceptible to flooding than it’s ever been. Flood mitigation, whether it’s on a federal level, like in New Orleans, or whether it’s on a property level, is pretty much mission-critical at this point,” he said.

Swiss Re estimates that a repeat of Katrina today would result in nearly $100 billion in insured losses in 2024 dollars, which is slightly lower than the inflation-adjusted loss of 2005, Mr. Pande said.

“The reduced physical devastation from a repeat of Katrina is largely due to the improved flood defenses and stricter building codes that have been implemented in and around New Orleans,” he said.

Fuente: Business Insurance

Enlace: https://www.businessinsurance.com/katrina-redefined-hurricane-risk-for-insurance-sector/